EL PASO, Texas (AP) — As children, twins Manuel Luis “Manny” Santoscoy and Luis Manuel “Louis” Santoscoy were best friends.

The El Paso Times (http://bit.ly/2ohLweY ) reports their mom dressed them alike and from their Central El Paso backyard, where they played cowboys and Indians, they dreamed of adventure every time they saw a plane overhead.

“We always looked out for each other,” Manny Santoscoy said Friday. “We did everything together.”

When they were drafted at the age of 18 while juniors at El Paso High School and shipped to the southwest Pacific during World War II, it would only make sense that they would seek to be together and protect each while fighting the Japanese. The two started off as excited new members of the U.S. Air Force, but within weeks were sent to the 24th Infantry Division, 34th Regiment, Company H, when replacements were needed.

Though some of their memories are not as sharp, the twins — who celebrated their 92nd birthdays Wednesday in El Paso — found their adventure, although perilous at times, in the service. And both vividly recall when Manny Santoscoy stepped in to provide first aid to his brother when he was hurt in a mortar attack on the island of Mindanao in the Philippines.

The 34th Regiment, as part of the 24th Infantry Division, is known for experiencing some of the most horrific combat in unbearable terrain in the Pacific War.

“My brother was in my squad and I was in another. His squad was a combat patrol and so I volunteered so I could go and be with him. We were in a mortar division shooting mortars. I was carrying the communication line throughout and the first thing I heard was ‘bang’ and another ‘bang’ between us,” Manny Santoscoy said.

He said many soldiers were hurt and medics started running to transport the injured on stretchers.

“I heard, ‘Let’s get out of here,’ as we were going down the hill and then I saw my brother in front of me. He was trying to run, but he was hurt,” he said. “We went down to a cornfield and there I attended to my brother. I saw he was wounded here (in the shoulder), and (on the side) and I gave him a pill to help coagulate the blood and I put a bandage on his arm.”

He also tried to patch up another soldier who had an injury affecting his lung and breathing.

“I don’t remember anything after, how I got back from the cornfield,” Manny Santoscoy said.

A few weeks later, Manny Santoscoy was injured while his brother was still recovering in a hospital tent.

“We were fighting the (Japanese) and we could see them shooting at us with anti-aircraft guns and we starting using our own mortar. I don’t know if I got hit by one of my mortars or theirs, but all of a sudden I was blown about 10 feet in the air and then landed on some grass. I don’t remember anything after that until I heard someone say, ‘Here’s another one.’ “

Manny Santoscoy was hurt in the stomach and ended up getting several clamps going down his torso.

Louis Santoscoy remembers being told about his brother and being taken to him in a Jeep.

“It’s hard to say because as you get older, you get melancholy. I saw him, he was pale and with the clamps. And I told him, ‘You’ll be OK.’ We never thought we would die in the war. We were kids,” Louis Santoscoy said.

The Santoscoys say they were on the front lines for six or seven weeks. Manny Santoscoy was the only one from his squad who returned. And Louis Santoscoy was among two or three survivors of his.

They are not sure if their instincts helped keep them alive, but they do believe they kept each other safe.

“Over there, you don’t feel anything; you just do what you have to do. We were just lucky to be alive,” Louis Santoscoy said. “I never thought about getting hit. We were concerned, but we were there for each other.”

Manny Santoscoy’s daughter, Sylvia Santoscoy McKillip, said her father used to say he came back to take care of his mother.

“He’d say he survived the war to take care of her. She was a stroke victim and that’s what he did for 12 years. They were our heroes,” she said.

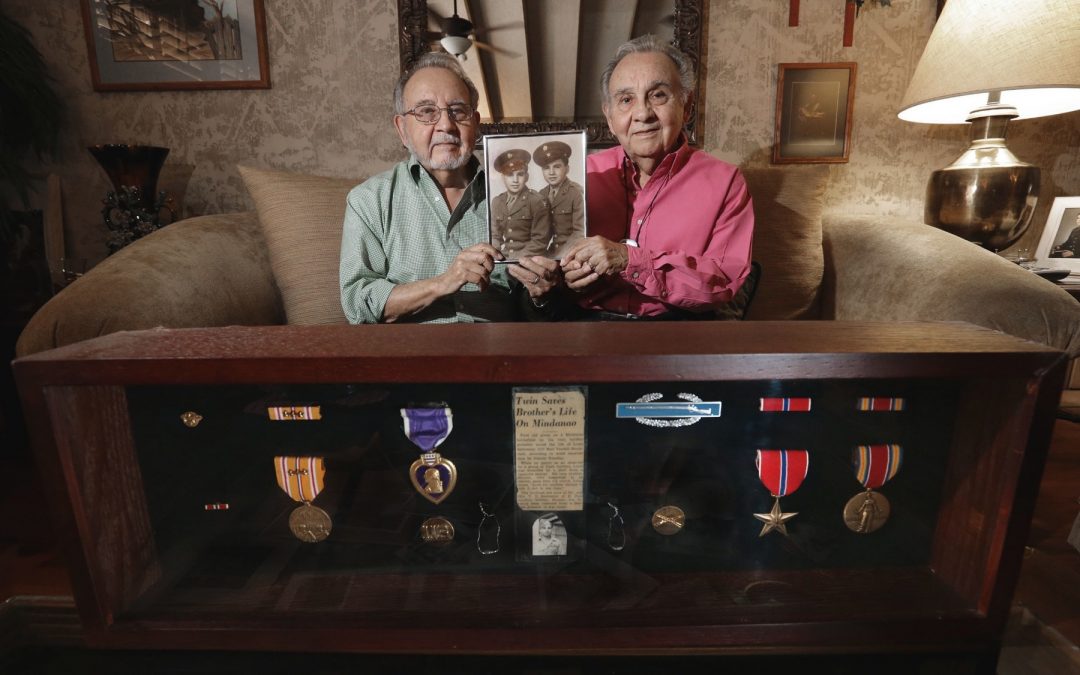

They were honorably discharged in 1945, a few months after the war ended. Both received the Bronze Star and the Purple Heart without fanfare. Manny Santoscoy’s medals are encased and hang in his home.

But both downplay the significance of their medals. After they returned, they both dabbled in different businesses, opening a flower shop in downtown El Paso and later a car shop. Eventually, the two earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees in education.

Manny Santoscoy was an educator and principal at El Paso schools for 23 years. And his brother was in education for 12 years before moving to California, where he became a counselor. He lives in Anaheim, California.

The two still try to get together, although distance has made it harder. But on Friday, they were happy to be side by side again, just like little kids: the last two remaining brothers in a family of nine siblings.

___

Information from: El Paso Times, http://www.elpasotimes.com

Copyright (2017) Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed.

This article was written by Maria Cortes Gonzalez from The Associated Press and was legally licensed through the NewsCred publisher network. Please direct all licensing questions to [email protected].

© Copyright 2018 Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.